Years ago, when apartment residents wanted to do laundry, they gathered their basket and detergent, loaded up their pockets with quarters and perhaps a good book or their Walkman and trudged downstairs to the dark, dingy laundry room. A few hours later, they would traipse back to their units, only to repeat the dreaded trip the following week. Nobody looked forward to doing their laundry (okay, let’s be real—that hasn’t changed), but modern technologies in the industry have made it much easier for residents to get this dreaded chore done.

21st Century Clean

Jim Gierach, sales manager at Universal Laundries, LLC in Chicago says the industry has changed over the 20-plus years he's been in the business.

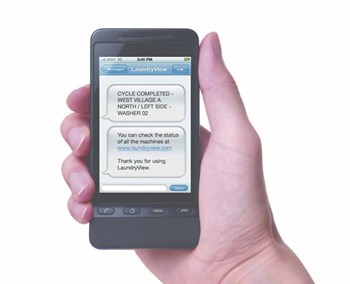

“It went from coin-operated equipment where you push the coins in, to a card reader, which is an online system where you typed in the number of the machine you wanted and the card started that machine,” he says. “Now, your card can be read right at the machine. In the future, you’ll be using your phone to pay.”

The washers and dryers themselves have changed throughout the years too, becoming far more efficient and environmentally friendly, saving both water and energy. As a result, buildings with common laundry areas are saving money. Although the exact savings vary from model to model, Sheffield J. Halsey, Jr., executive vice president of marketing for laundry equipment company Mac-Gray Corporation says that high tech machines have cut operating costs significantly, potentially saving thousands of dollars each year in water, sewer and energy bills.

“Most high-efficiency washers tumble the clothes in a front-loading unit, rather than submerging them in water as in top-loading units,” he says. “Because less water needs to be heated, energy consumption is reduced during each washing cycle. Plus, these front-loading washers extract much more water from clothes during the spin cycle, which translates into big savings of time and energy on the drying side.”

Benefits of a Laundry Room

If your building doesn’t have a common laundry room and isn’t receiving the financial benefits, now might be the time to consider one. According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, converting from an in-unit laundry to a common area laundry room allows an owner or manager to reap the savings and other benefits without having to become experts in laundry services for their properties. In-unit washers and dryers use a lot more water, drive up overall utility costs, and can lead to flooding or other water damage between units. In-unit connections also require more costly plumbing, venting and electrical wiring.

To show the difference in savings with common versus in-unit machines, the Multihousing Laundry Association in Raleigh, North Carolina, recently completed a national study of water and energy consumption in multifamily housing and found that residents with in-unit clothes washers used 3.3 times more water for laundry than residents in apartments with community area laundry rooms. The average washing machine water use on- and off-site for residents with in-unit laundry facilities was 227 gallons per unit per week, while the average washing-machine water use on- and off-site for residents with community area laundry facilities was 69 gallons per unit per week.

Not only does having a common laundry area benefit the building’s bottom line, but it’s an attractive amenity to current and future residents.

“Residents are looking for more conveniences, more dependable services and more amenities, and laundry facilities can play a major role in how they perceive the quality of life in a housing community,” says Halsey.

How it Works

In most cases, a building with a laundry facility in-house has contracted with a laundry company in some form or other. The laundry company usually leases out the room, installs and repairs the machines, and collects and disburses the revenue back to the building. The building or condo association doesn't need to make any significant capital investment into the room, and aside from a daily check and sweep of the room, usually carried out by the building engineer or a staff member, the laundry company takes care of maintenance.

The amount of commission the building or association gets from the laundry facility can be based on such items as the number of units in the community, the cost of washing and drying and the cost of the machines themselves. “In the old days, the revenue would be split 50/50 or 70/30, but now we work on a fee-based scale,” says Geirich.

According to Steve Breitman, president of SEBCO Laundry Systems in Green Brook, New Jersey, there are three common types of agreements: the laundry lease agreement; the license agreement; and the management agreement.

"The most popular and widely used is the laundry lease agreement," says Breitman. "It creates a basic relationship between the property and the laundry company. Typically, leases are five to 10 years in length and the term is most driven by two factors: the equipment cost and the return that the laundry company can expect from the collections. Additionally, if there is fix-up included with the agreement—painting, lighting, tile floor or other amenities—the term tends to be to the longer side."

Breitman goes on to explain that the license agreement provides similar terms to a lease agreement, but he says that in some instances laundry companies do not want to enter into license agreements because it may not afford them adequate security.

"A management agreement has limited application," says Breitman. "The revenue is directed to the property and the board receives payment from the manager. There are a number of variations to this type of agreement to fit the specific needs of the property."

Contract Considerations

So what kind of agreement suits your building's needs? Most pros agree that you need a specific agreement written for the specific needs of your building, not a boilerplate, one-size-fits-all contract. Engaging a service provider to handle your association’s laundry facility is an important process, and your contract with your chosen vendor should outline the expectations of both parties during the time period of the contract - including maintenance, service and payment.

Dawn L. Moody, attorney at law with Keough & Moody PC in Naperville says the most important part of a condo community's laundry room contract is not having what’s called ‘the right of first refusal’ clause in the contract at all. “And if an attorney hasn’t reviewed a laundry room contract for an association,” she says, “it’s almost a certainty that it’s in there.”

So what's the right of first refusal? “When a contract expires and the association wants to terminate it and find another laundry company,” Moody explains, “the right of first refusal stipulates that they must give the old company a look at the new company’s contract, so they can see if they can meet those terms.” If the old company can meet the new contract terms, the association is legally obligated to continue the contract with the old company, she continues. “If an association signs with Company B before giving Company A right of first refusal, the association is in breach of contract and may have to pay liquidated damage provisions to Company A.”

Moody remembers one such case that went on for five years. “The association continued using Company B’s services, but it was a very long litigation with Company A, and a lot of money was spent on attorneys’ fees.”

Most laundry contracts are long-term—often 7 to 10 years—and there is only a very small window of opportunity to terminate the contract before it automatically renews. “Most associations aren’t on top of looking at their laundry contracts,” Moody says. “And even if they are in that window, the old company still has right of first refusal if it’s in the contract.”

Your association's attorney can work with your board and manager to create a contract that eliminates this term or, in the case of a brand new association, make sure it’s never put in. “Associations should also want a more liberal termination contract, with 60 days and no cause,” says Moody, who also advises associations to keep an eye on the contracts and send a notice when they are preserving their right to cancel the contract. “Then, if they want to, they can renegotiate,” she says.

When the contract is up and it's time for renegotiation, Breitman says there are three main reasons that properties elect to retool their agreements: money; modernization and updated equipment; and beautification.

According to Breitman, "Today's most requested features are card systems that allow the residents to use a laundry card, rather than coins."

Not all renegotiation leads to a resigning of the contract. Perhaps the new rates are too low for the building or too high for the vendor, or perhaps the building was not satisfied with the service they received from the vendor. As with any separation or dissolution of business, determining who owns what in the laundry room is critical.

As a rule, say the pros, the plumbing apparatus and fixtures obviously belong to the building—so the only thing most contracts allow the laundry vendor to remove is the machinery. The space should be left clean and swept, ready for the new vendor to move their equipment in with minimal disruption or inconvenience to residents.

Maintaining a laundry room that is safe, reliable and comfortable generates revenue and makes the residents happy —and that's what owners and managers want. With an eye to new technologies and a conscientious approach to contracts, you can give them that without getting taken to the cleaners.

Lisa Iannucci is a freelance writer and author living in Poughkeepsie, New York.

Comments

Leave a Comment