Most people assume that as soon as they buy their first home, they will finally have the freedom to paint their decks purple, to hang fluorescent window treatments and colorful sconces, or to litter their lawns with political or yard sale signs.

But that much freedom is rare, if not obsolete if you live in a condo, a co-op, a gated community or any other shared living space.

It’s in the Rules

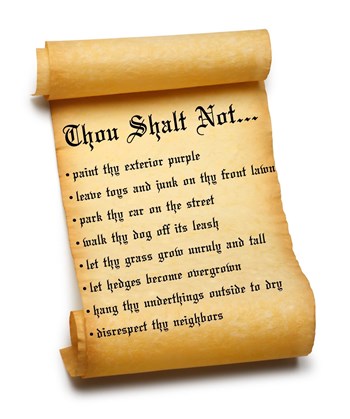

Most condo and homeowner associations have stringent guidelines regulating the aesthetics of their communities. These can be as detailed as which type of siding and shutters homeowners may use, what paint colors are allowed, what types of plantings and other landscaping or ornamentation are permitted, and even what kind of mailbox owners can put out front.

It’s part of the territory of living in a community association, and the idea is that a tidy, uniform, nothing-too-crazy appearance raises property values—and that anything that steps outside those parameters will put prospective buyers off and may cause values in the area to plummet.

But these rules aren’t random, and breaking the rules isn’t an option if you want to live happily ever after in the home of your choosing. However, there are ways to preserve your aesthetics and your creativity without overstepping authority.

What’s Allowed, What’s Not

The rules vary depending on the type of building you’re living in. In high rises, many of the rules apply to window treatments, because those are what’s most obvious from the outside, says Michael Kim, principal of the law firm of Michael C. Kim & Associates in Chicago. In a high rise, if you have a balcony, then there will probably be rules discouraging anything that may be distracting or offensive, such as Christmas ornamentation and inflatable decorations or signage.

Other associations restrict where you can attach a lock box, while high-rise buildings are very restrictive about what can be outside the door and what can be placed on the door when it comes to holiday decorations and welcome signs. Some condo and homeowner’s associations even have restrictions for satellite dish installations. The government says the association must allow them, but they can still restrict where they are placed.

Another huge issue when it comes to aesthetics is political signage on lawns and in windows. In fact, it’s become such a hot button topic, that there are numerous lawsuits about the signs—and there still isn’t a real resolution.

The problem is that if there’s a sign on a lawn or in a window, no onlookers can really tell whose sign it is. And if you personally don’t support that candidate, you probably don’t want other people thinking that you do. But on the other hand, Americans have freedom of expression—which conflicts with the government banning their signs, which are seen as a First Amendment right.

In most cases, the buildings have no problem prohibiting “for sale” or “for rent” signs, because that’s viewed as commercial rather than political.

“Some courts tend to favor political speech over commercial speech,” Kim says.

In 1994, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a law in Missouri prohibiting the signs in private homes. Then, the Supreme Court rejected the ordinance saying that yard signs were “a venerable means of communication that is both unique and important.” They explained that residential signs are a convenient form of communications.

More recently, legislation in Arizona passed prohibiting planned communities from banning political signs on your own property—as long as it’s 45 days before and up to seven days after an election. This followed similar legislation in California and Maryland.

Issues in Illinois

In Illinois, the rules aren’t set in stone. The Illinois Condominium Property Act (ICPA), Section 18.4, allows condo boards to adopt their own rules governing property use. But it also says that the rules that the condo board adopt must not impair on any rights protected by the First Amendment.

The condo act was also amended to allow unit owners to fly military or American flags on building exteriors near their units. Associations are still allowed to regulate the flag’s location and size. They may also limit the number of signs per residence.

Homeowner and condo associations can fight all of this and take this a step further arguing that they shouldn’t be constrained by the First Amendment since the associations are considered to be private parties that don’t need to follow the state or federal rules when it comes to free speech. That amendment only protects people from the government’s interference. It’s difficult to justify giving up your free speech to live within an association, but for most people, it’s worth it.

It helps to think about the whole situation differently, says Angela Falzone, consultant with Association Advocates, Inc., a property management consulting firm in Chicago.

“A condo is a mini-government that comes with rules—we are free to drive a car, but we stop at stop lights or face consequences,” she says. “Those restrictions are understood when we get our driver’s license and buy a car. Buying a condo is no different. If you don’t like the limitations put on your residence, then a condo is not for you.”

Following the Rules

Before purchasing your home in a multiple family residence that has a declaration, you sign a waiver at the closing stating that you understand what you are doing, that you agree to abide by the documents and that you have read all the papers and fully intend to comply.

So for the most part, you can find out what you’re allowed to do before you purchase your home. That’s because the rules are usually laid down when the association is formed by way of the declaration—although they may be changed as the association sees fit—for example, when someone paints their unit an ugly shade of purple. But there needs to be a vote in order to change the declaration.

“The board may add more aesthetic restrictions as time goes on, but general rules start with the declaration and bylaws of an association,” Falzone says. “In aesthetics—things like window coverings, items that can be stored on a patio, holiday door decorations—these restrictions can be in either the documents or dictated later by the board in rules and regulations.”

Before the declaration is written—or when there are changes that need to be made the board should be very specific when it comes to the aesthetic rules so that no residents can try to get around them.

It sounds simple enough, but sometimes, the unit owner may not like the rules, or think that they aren’t too clear.

In one Chicago-area community, an owner moved into a townhome and proceeded to take out all the landscaping in front of her unit—and replace it with her own, Falzone says. But the problem was that in townhomes, uniformity—even in landscaping—adds value. Additionally, the landscaping was on common ground and didn’t belong to the owner.

“The situation festered, went to court and the owner refused to pay assessments because of her anger, and she was almost evicted before paying in full. The errant landscaping, however, remained,” Falzone says. “As a manager, I assisted the board in revamping all the landscaping, worked around her changes and put in rules that anyone tampering with their plantings in the future would be held accountable, and life went on.”

Pick Your Battles

In Falzone’s case—and in others—if there is a problem, the board needs to be careful to avoid a legal battle of wills. They should first document the violation, and notify the owner of the offensive activity in writing. Give them a specific number of days to remedy the situation, and specify which section of the documents or rule is being violated. They should also let the owner know what the penalty will be if the situation is not remedied. This can range from a fine to an eviction or lawsuit.

The unit owner may try to challenge the rules, but they probably won’t win, Kim says. If it says in the bylaws that all window treatments must be in a neutral color, the unit owner may try to fight it but they’d probably lose.

“The board would have to prove that they have a reasonable request. But if it’s in the declaration, it’s much more difficult, if not impossible to challenge,” Kim says.

Still, there can be exceptions made, and these won’t necessarily do damage in terms of property value. Exterior access ramps for a disabled owner, or other alterations that may not be the most lovely thing aesthetically—and necessary for the use and enjoyment of the property—are usually still allowed as long as they go through the board.

Since condos aren’t public property, the board doesn’t have to legally accommodate handicapped residents. But if a request for a modification is brought to the board for a disability, the board is obligated to consider or allow the change at the owner’s expense, Falzone says.

“This would be within reason, and the negotiations should be under the guidance of the attorney,” she says.

Other exceptions may be made for aesthetics which are grandfathered in, and should be made on a case-by-case basis. These types of conflicts generally come from generous developers who allow something at the closing to get the sale—but it’s later considered not in compliance. These may be grandfathered in because of the original approval process.

But, Falzone says, “A situation like this causes animosity for years to come.”

The easiest way to prevent a board or an association from getting into a legal battle with an owner is to clearly explain the rules from the beginning.

“When people come into the building or the neighborhood, they should be told that there are certain things they must do,” Kim says. “The ideal thing is to work on education at the starting point.”

It’s important to remind everyone of why the boards are making these aesthetic decisions. Most of them relate to improving the overall property value in the communities, whether it’s a high-rise community or a gated community.

“It’s to not only prevent people from doing outrageous things because it might offend their neighbors, but it also may negatively affect property values,” Kim says. If a homeowner lets their weeds grow and doesn’t do anything when the paint on the outside of their home starts to peel, it makes the community look like it’s been abandoned, and could drive away qualified buyers when the time comes.

Danielle Braff is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Chicagoland Cooperator.

Leave a Comment