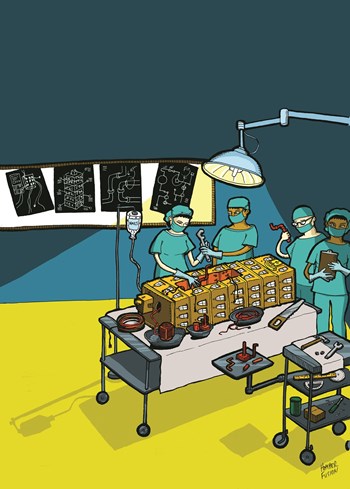

If you think about it, a multifamily building isn’t that much different than the human body—both house important complex operating systems and organ-like pieces of vital equipment, both take in fuel and produce waste, and both require regular check-ups and a good maintenance program to stay healthy and thriving.

Checking In, Checking Up

And just like humans need to see doctors regularly for updates on the heart, lungs and eyes, buildings need to have examinations of their systems as well, with checkups required for HVAC/chillers, plumbing, electricity, and the building envelope.

Steven Maze, principal of Elara Engineering, an engineering consultant firm located in Hillside, says the laundry list of what should be checked includes mechanical (i.e. heating, ventilation and air conditioning) systems; plumbing (domestic hot water, domestic cold water, including a pressure boosting pump system in high rises), waste and vent piping; electrical systems (motors, lighting, wiring, panels and overcurrent protection such as fuses and circuit breakers; and fire protection mechanisms like sprinklers.

The problem is, no two multifamily buildings are alike, which is why each building should have a solid maintenance plan in place.

“Heating for example can be via electric or natural gas based, air/water/steam,” says Maze. “Similarly, cooling can be via a central chilled water system or small, self-contained air conditioners serving each individual unit. Depending on the specific system and equipment, there are daily, weekly, monthly, annual and even 10 year maintenance tasks.”

Peter Power, vice president of Klein and Hoffman, a Chicago-based structural engineering firm, warns not to forget about things such as fire alarms, elevators, security systems, roofing, and exterior systems (such as windows, doors, patios, steps, etc.)

“The individual systems listed above, when fully operational, work independently and in many cases in unison with each other in order to provide a safe and comfortable environment for occupants,” he says. “Instabilities in one small aspect of a system can cascade into a system-wide or building-wide problem. All systems must function properly to provide a safe and inhabitable environment.”

Robert Meyer, director of engineering services for FirstService Residential, a property management firm in Chicago, says the primary operating systems that are located in the majority of multifamily buildings in the company’s management portfolio include both domestic plumbing and the HVAC system.

“A very basic explanation would be that the HVAC system provides comfortable heating and cooling during the appropriate seasons and the domestic plumbing provides hot and cold water into each unit within the building,” he says. “There should be monthly inspections on all systems with moving parts. In addition, there should be bi-annual inspections on the entire piece of the equipment, which includes electrical connections, and associated hardware. We recommend doing an entire equipment inspection prior to the seasonal start-up.”

By Definition...

Here is a brief explanation of how these systems work to serve the building:

HVAC: Provides adequate heat, cooling and ventilation in accordance with building, mechanical and energy codes. The HVAC system can consist of boilers, chillers, cooling towers, air handling units, radiators, fan coil units, window AC units, pumps, valves expansion tanks, etc. Although piece of equipment serves a different function, they all operate to maintain thermal comfort and a healthy level of ventilation for the occupants in the building.

Plumbing: Provides hot and cold potable water to sinks, showers, dishwashers, washing machines, etc. The plumbing system also serves to properly drain used potable water and storm water from the building to the city sewer lines.

Electrical: Provides power with adequate protections to lights and energy consuming systems throughout the building. The electrical system consists of service transformers, main distribution panels, switchgears, disconnects, and distribution subpanels.

Life Safety: Provides adequate protection to the occupants in the event of a fire, power outage or other emergency. Life protection systems include but are not limited to fire pumps, sprinkler system, fire alarm system, stairwell pressurization fans.

Building Envelope: Protects the building interior from the weather.

When Issues Arise

Each piece of equipment associated with one of the main building systems has an anticipated useful service life. The useful service life is the duration (in years) in which the equipment is expected to properly operate. The useful service lifetime varies by equipment and is typically included in the equipment schedule provided in a reserve study.

A reserve study is a long-term capital budget planning tool which identifies the current status of the reserve fund and the status of all the major capital systems maintained by the association and their useful life spans. Mechanical and plumbing issues are oftentimes due to deferred maintenance or reliance on these systems that are well beyond their useful life expectancy.

Ralph Schmidt, president of Schmidt Engineering Inc. in Wauconda, says his larger clients (those with multiple buildings) tend to have an ongoing maintenance program that includes regular inspections of their properties, and recommendations on upkeep, repair and replacement. “The smaller owners tend to call us on an as-needed basis; when problems occur or if they are planning to make changes,” he says.

Maze says there aren’t major differences between larger and smaller buildings in terms of maintenance schedules and potential problems, but again, it’s specific to the types of systems installed.

“In general, we see small multifamily buildings that have systems similar to larger multifamily buildings and therefore no major differences,” he says. “We also see small multifamily buildings with systems similar to single-family homes. These may be less maintenance intensive given their relative simplicity.”

Regular maintenance is an important factor in providing a safe environment as well as continued operation but it’s something that an expert is usually needed for as major building system maintenance and repair can be complex.

“Some buildings regularly inspect systems, while other buildings implement preventive (monthly) maintenance schedules to avoid problems,” Power says. “The schedules ultimately depend upon the owner or building association and building’s code—some systems require seasonal check-ups, while others have yearly, quarterly, or even monthly check-ups.”

According to Power, some differences include the size and height of buildings, complexity, the number of occupants and operation schedules.

“Smaller buildings often do not have in-house staff to repair small items or to provide annual maintenance to prevent the small problems from expanding in scope,” he says. “Meanwhile, larger buildings may require more frequent maintenance and attention as they often operate 24/7.”

Meyer agrees that the most common building system problems result from a lack of preventative maintenance or deferred maintenance.

“By not maintaining the system this can result in mechanical breakdowns, which then result in unplanned and costly expenses to the association,” he says. “Some preventative measures FirstService Residential take include conducting monthly inspections. However in some cases there are warning signs, such as strange noises, weird smells, and vibrations that mean it is time to fix or replace a system.”

Power notes instabilities in a system can cause system-wide or even building-wide problems and that can lead to costly fixes. “There are times when an individual system is not fully functional and unless properly maintained, will fail at some point,” he says. “Failures and outages are primary problems with any system.”

There are numerous ways in which equipment can degrade and fail over time. Equipment that is properly maintained since installation should be able to last for the duration of its anticipated useful service life.

Taking Responsibility

Everyone responsible for the buildings long-term life play a role in maintaining the building, be it the superintendent, staff, manager and board but Maze notes that it really all begins with a proactive board and management.

According to Meyer, ultimately, the board delegates building maintenance to the property management company, which may or may not include a building engineer.

“Most commonly in high-rise buildings, the building engineer handles all of the building system maintenance including scheduling service providers and outside contractors to fulfill the preventative maintenance under contract,” he says. “In the example where there is no building engineer, it is up to the property management company to coordinate service providers and uphold service contracts.”

Power adds that property and community association managers can arrange for repairs as needed, or delegate the work to contractors or specialty firms. “Smaller maintenance items can be handled by in-house staff,” he says. “Larger maintenance items should generally be handled by specialized contractors or engineers. The maintenance for building systems is based on the particular system as well as the building’s maintenance plan.”

In mid-rise and high-rise buildings, the association is usually responsible for the repair and maintenance of the common building infrastructure and functionality. In smaller buildings, many of the systems (e.g. HVAC) become the responsibility of the individual unit owner. However, a multifamily building’s board, unit owners or shareholders have a fiduciary responsibility to act in the best interest of the building.

All the building professionals we spoke with agreed that keeping building systems up and running properly—and getting optimal performance out of them over the course of their useful lives—is a much easier task when boards and managers have at least an overview of what those systems are, how they work (both together and separately) and what their most common vulnerabilities are. That knowledge, combined with a team of trusted professionals, can save money and eliminate hassles in the long run.

Keith Loria is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Chicagoland Cooperator.

Leave a Comment