On any given day or night in Chicago, a stranger walks up to Craig Perry’s North Lawndale home, opens Perry’s door, hangs up his or her jacket, and relaxes in Perry’s bed while watching Perry's television and using his WiFi, before disappearing again without a trace. In a few days or weeks, the pattern repeats itself with another stranger, and another after that.

The parade of outsiders pleases Perry, 54, to no end. It’s thanks to these strangers that he was able to stop working as a computer consultant—and instead, is able make an income renting out his spare three-bedroom, one bathroom apartment in his brick two-flat via Airbnb Inc. He doesn’t plan on going back to his day job anytime soon—or stopping the rotating cast of travelers passing through his apartment. “There were hardships at the place I was working for, and I found that this was a wonderful alternative,” Perry says.

An Ideal Idea?

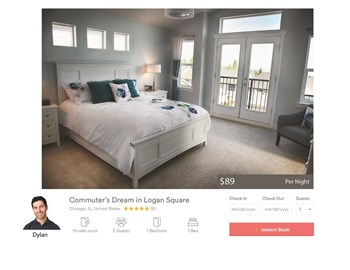

The media and political buzz surrounding so-called “home share” or “short-term rental” websites (primarily Airbnb, but also other similar services like Homeaway.com or VRBO.com) has been on the upswing over the last year or so. It sounds like a perfect arrangement; You go on vacation, and rent out your home while you’re gone—you get a house sitter who pays real money, instead of the other way round. Or, you stay home, and rent out your spare room—making a few hundred (or even a few thousand) dollars without doing anything more than washing your extra set of sheets and wiping down the counters. It’s all part of a growing trend called homesharing, which is taking Chicago (as well as other “destination cities”) by storm.

In the Chicago-area, you can rent anything from a “quiet place in Wicker Park” that the owner describes as a spare room with some storage and a fold-out bed for $45 per night to a $3,000 Lakeview luxury high-rise with a big-screen theater projector, a 24-hour business center and a full gym. Indeed, for renters and for those doing the renting, when it comes to homesharing, the sky's the limit in terms of what you can get for your money, and how much cash you can make.

But while thousands of apartment owners in cities like Chicago, New York, Boston and San Francisco love being able to monetize their units by renting an extra bedroom (or even their whole place, if they're out of town) to a visitor or tourist, condo and HOA boards and management are typically less enthused about the trend. A constant stream of non-resident visitors raises security concerns, adds wear-and-tear to common areas, and complicates the enforcement of house rules. Depending on the city, short-term rentals may also run afoul of zoning and hospitality laws.

Homeshare History...and the Law

The biggest player currently in the homesharing game is without question San Francisco-based Airbnb Inc. Founded in 2008, the service allows anyone to list their house, condo, spare room, couch, boat, treehouse or any other living area for short-term rental. More than 9 million people in 34,000 cities have checked out Airbnb—with more than 500,000 listings across the world—so this trend is certainly not shrinking or going away.

In fact, according to the company, on December 31st, Airbnb had its biggest night in its history, with nearly 550,000 travelers using the company to stay in more than 190 countries. Of those, 91,000 were guests using Airbnb for the first time, and 22,000 hosts were new, too. That’s compared with five years ago, when only 2,000 people used Airbnb on New Year’s Eve.

In Chicago, a default position of condo associations generally doesn’t allow residents to openly do these short-term vacation rentals, says Jim Stoller, president of The Building Group, which manages more than 7,000 buildings in the area. So unless they purposefully opt in to allow residents and owners to do Airbnb and other short-term rentals, the assumption is that most condo and HOA bylaws forbid these short-term rentals. This was put in place just in case boards and associations didn’t know about Airbnb and other homesharing companies—and didn’t catch onto the idea in time to prevent them from happening, Stoller says.

And to his knowledge, those that do know about homesharing in Chicago still haven’t flipped the switch and opted in to allow their buildings to do it, Stoller continues. “I don’t know of any buildings who feel it’s a good idea,” he says. “I think that most people would look at this as a negative unless they’re personally making money.”

That being said, Stoller has seen his share of condo owners who have tried to do Airbnb—regardless of whether they're allowed to do so or not. “Historically, we've seen people use it and do fine – but sometimes, they’ll rent [their unit] and the renter will use the unit for a party, and people will throw up in the hallways.”

Home vs. Hotel

Hallway vomit is pretty gross obviously, but Stoller says the issue with homesharing in condo communities goes significantly deeper than just spot-cleaning the carpet. “The bottom line is that these buildings are not set up to be hotels.”

Which is to say, most buildings don’t have the security that hotels have; they don’t have the doormen, they don’t have porters and moving carts to get people and their luggage in and out of their rooms without damaging the hallways and the elevators, Stoller says. They also don’t have the sprinkler systems that hotels have, which is a very big deal.

“It’s a different set of expectations,” he says.

When Airbnb first arrived on the scene in 2008, Stoller says his company received many complaints that condo owners were illegally allowing their units to be rented for the short-term. So his company immediately set up rules against this, and cracked down on the practice.

“But people still tried to sneak in and do it,” Stoller says. “In the past year, we had someone who snuck someone in, and he said, ‘Well, I was making so much money.’”

Stoller's company fined him, but since he had been making thousands of dollars per month, the man just paid his fine—and continued operating as an Airbnb rental. So Stoller's group upped the fine to thousands of dollars—and this time, they finally shut him down.

Jim Saccone, co-owner of A Saccone & Sons, a family-run business based on the North Side of Chicago offering real estate services including management, rentals and sales, says residents have approached him about operating Airbnb rentals out of their homes, but he’s always said “no,” because he worries that other tenants wouldn’t be happy about essentially having hotel operations being run next door to their home.

“I had a girl who was living in one of my apartments for about two years, and she threw the idea at me that she wanted to keep the apartment and rent it out on the weekend, and sometimes during the week, and I told her ‘no,’” Saccone says. “But I believe that we manage about 1,000 apartments, so I imagine that it’s still going on in some of them—it’s pretty rampant.”

Saccone says he thinks the idea of homesharing gets into someone’s head when some of his tenants get transferred out of town but they want to keep their apartments—so they start doing it on the sly. “But I don’t think it’s right,” he says. “You’re renting out your space like a hotel room.”

Perry, on the other hand, says he does his Airbnb business legally. He owns his small building and it’s zoned for vacation rental through the city of Chicago, he says. He pays $250 for a two-year license, and he pays the applicable taxes whenever he rents out the room. In order to get this license, a residence must contain six or fewer rooms for rent, and the license is required for any short-term vacation rentals. Plus, renters are required to obtain fire, hazard, liability and general commercial liability insurance, and they must maintain current guest registration records.

Cracking Down?

Perry is one of the rare people who has done everything legally with few issues, he says. But he may be in the minority. In New York City, according to New York City Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, as many as 75 percent of Airbnb reservations are illegal. There aren’t current records as to how many in Chicago are operating illegally, but chances are it’s close to the same as in New York, since the standards for legal operations are similar.

In January, a New York City housing court judge evicted a rent-stabilized tenant for using Airbnb to profit off of his rental while he and his family were living elsewhere. It is the first recorded case of someone being evicted for using the service.

Still, Airbnb has been very good to Perry, he says, though this winter has been a little slow, as not too many visitors have been wanting to experience the grand allure of a Chicago snowstorm and below-freezing temperatures.

His biggest problem so far—aside from the expected slow season? Glittery women, he says, laughing. “I really don’t have major problems, but there was a glitter party one time, and glitter is really hard to eradicate,” Perry says. “I still find glitter. But if that’s the biggest of my problems, it’s not so bad.”

And things are changing quickly to help draw some hard lines through the legal grey area homesharing has occupied since it became an issue. For example, up until February 15, Airbnb was blamed for not collecting taxes from many of its hosts – and for essentially allowing its members to be used as illegal hotels, taking away business from real, legal hotel businesses. Last year, they began collecting taxes in San Francisco, Portland and California, and they’re continuing this practice to more cities including Chicago and Washington. The company just notified Perry that they’re going to tack on a 4.5 percent tax for the Illinois vacation rental license tax starting February 15– which up until now, Perry had been passing along to his renters directly to make up for the amount that he had been paying to the state.

In a presentation of new tax initiatives to the Finance Committee in November, Budget Director Alexandra Holt says the vacation rentals had only produced $200,000 in annual tax revenues, but the new taxes would add another $1 million in revenue to the city of Chicago, though it would still be difficult to collect the taxes from those who would continue to arrange their own vacation rentals.

So now, Perry’s thinking about reducing the rent to make up for the taxes that his renters will have to pay. All-in-all, Perry realizes that he’s one of the lucky ones when dealing with Airbnb and with his legal options. “It’s much easier to do this when you own your own building,” he says.

Still, people are using Airbnb and other vacation rental services, regardless of whether or not they own their own buildings, rent their homes or own a unit within a building.

Most are doing it regardless of the legality of it all because this is such a lucrative and seemingly easy way of making money.

Danielle Braff is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Chicagoland Cooperator.

Leave a Comment